Managing Risk when Rebalancing into Bonds

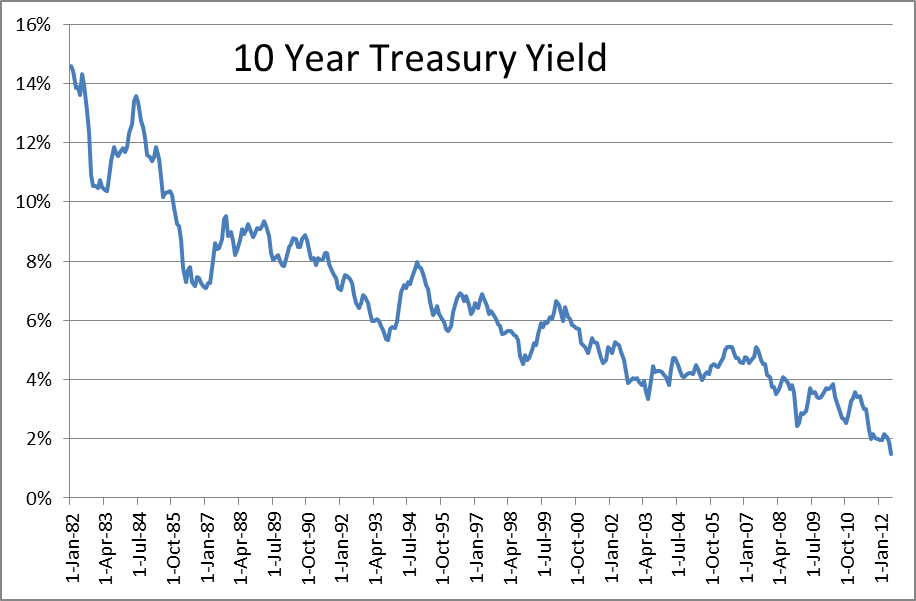

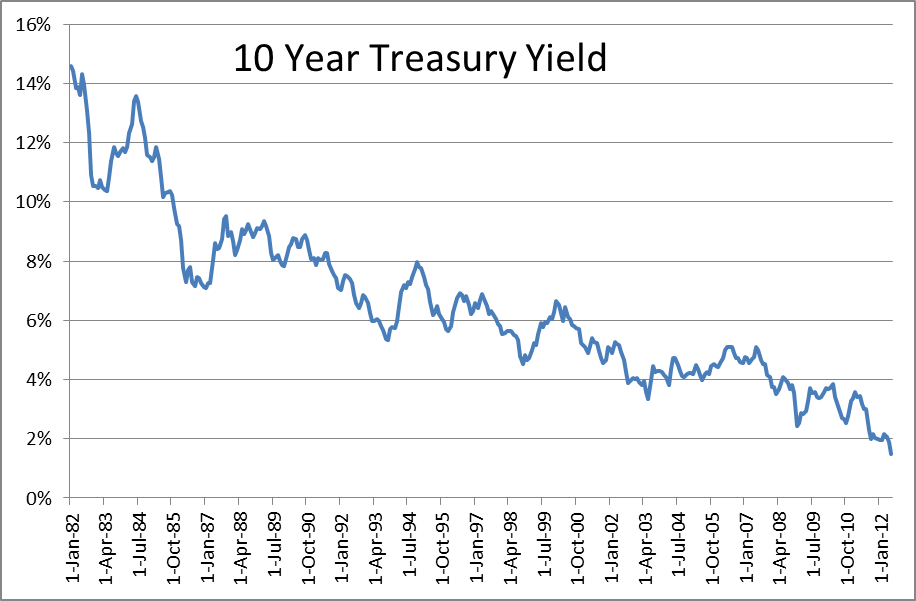

It’s been hard to miss the impressive run up in stock prices over the past 12 months – the Dow Jones Industrial Average, for example, gained 22% in the year ended May 31 – and for some, that creates a conundrum. Writing in the New York Times, Paul J. Lim discusses the challenge of rebalancing from stocks to bonds when bonds are looking expensive (“Rebalancing the Portfolio? Don’t Break the Seesaw”). This is an understandable concern, since the sharp rise in stocks relative to bonds has begun crossing rebalancing thresholds and triggering the sale of stocks and purchase of bonds. And yet bonds look like an expensive place to be adding new funds. Bonds benefit from falling interest rates and, as the chart below illustrates, interests rates have been falling for 30 years.

As you can see, the rate on the 10 year Treasury bond has fallen from 15% in 1982 to barely 2% now, which, unless you think rates are likely to fall further, means that we’re at the end of a 30 year bull market in bonds. In other words, the party is over for bonds. Does that mean that rebalancing into bonds is a mistake? Not necessarily. The key is to understand the nature and sources of risk in owning bonds.

The option many people choose when looking for bond market exposure is to choose a “total bond market” index mutual fund. This is often the only choice in company 401(k) plans. However, these often offer less diversification than one might think, while introducing other sources of risk. In his New York Times piece, Lim quotes legendary Vanguard founder and indexing pioneer John Bogle saying that total bond indexes “are deeply flawed — and that’s coming from an indexer.” Why is this? To answer this question, let’s review the two main sources of risk associated with owning bonds.

Interest Rate Risk

A bond is a fixed obligation of the issuer – whether that issuer is a government or corporation – representing a loan from investors. While there is an implicit yield or interest rate associated with a newly-issued bond, that initial rate is not guaranteed. The bond issuer makes two simple promises to the buyers of its debt. The first is to pay a periodic dollar amount, known as the coupon, a term that dates from the time when bonds were physical documents that had “coupons” attached that investors would clip and submit to the company in order to receive an interest payment. The second promise is to repay the original loan amount, referred to as the “face value” or “par value,” at the specified maturity date. Because a bond issuer only promises to pay a periodic dollar amount and not a guaranteed interest rate, investors buying and selling on the open market will bid the price up or down in order to buy at a price that will make the coupon payment’s implicit yield match prevailing interest rates. Here’s an example:

Widget Inc. issues a new bond at a time when the prevailing interest rate is 5% and the bond is bought by Jane Doe.

$1,000 – “face value” at which the bond is issued.

$50 – annual “coupon”

5% – yield at issue

A year later, Jane wishes to sell her Widget bond on the open market. Due to a rise in expected inflation and/or policy changes at the Federal Reserve, the prevailing interest rate at this time is 10%. Will buyers pay Jane the $1,000 that she invested in this bond? The answer is no. Instead, prospective buyers will look at the $50 annual coupon that Jane’s bond pays and say to themselves, “if I pay $500 for this bond, the $50 annual coupon payment will represent a 10% interest rate, which is what I can earn on comparable investments.”

Jane sells her bond on the open market.

$500 – price offered by buyers.

$50 – annual coupon

10% – current yield

NOTE: The above is merely an approximation. Technically, the current price of the bond will be the “present value” of all remaining coupon payments plus the present value of the face amount to be returned at maturity, all “discounted” at the prevailing interest rate.

What all of this means is that, all other things being equal, falling interest rates will cause investors to bid up the price of a bond and rising interest rates will cause investors to drive the price down. As we noted when we introduced the chart above, the general trend in interest rates has been downward for 30 years, giving the bond market a steady tailwind. But with rates now so low, the trend is likely to reverse at some point, raising the specter of falling bond prices and outright losses.

An important point to make is that the magnitude of any price change for a given change in interest rates is a function of the number of years to maturity. Bonds with long maturities will exhibit large moves in response to rising or falling rates while bonds with short maturities will experience relatively small price changes for the same change in the prevailing rate.

Default Risk and Credit Quality Risk

All bonds contain some risk that the issuer will default on its obligation. This risk may be large or small and will impact the yield that investors demand. This is not a static risk factor as the fortunes of a company or municipal government can change many years after a bond has been issued, causing price changes in the open market. The recession of 2008, for example, struck financial companies particularly hard, causing the price of their bonds to fall precipitously in the open market as investors demanded higher yields on their debt.

Investors turn to bond rating agencies for assessments of the soundness of a given bond issuer. Standard & Poor’s, for example, offers bond ratings that range from AAA to A, BBB to B, all the way to D. Anything below BBB is considered “non-investment grade,” also known as “junk” or “high-yield.” As attractive as “high-yield” may sound to income seeking investors, when you hear “high-yield,” think “junk.”

Managing Risk in Your Bond Portfolio

One of the first things to remember when buying bonds, as in all investing, is that there is no such thing as a “free lunch.” When investors “reach for yield” by buying longer-maturity, higher-yielding bonds, they are taking on more interest rate risk and may suffer losses if prevailing rates rise. Likewise, when investors seek higher yield by buying lower credit-quality bonds, they run the risk of loss from default or a rating agency downgrade. For example, many investors who were drawn to the high yields of Lehman Brothers bonds found their holdings wiped out when the company collapsed in September of 2008.

Here are the three primary methods for minimizing risk in a bond portfolio:

- Diversify

- Keep maturities short

- Keep credit quality high

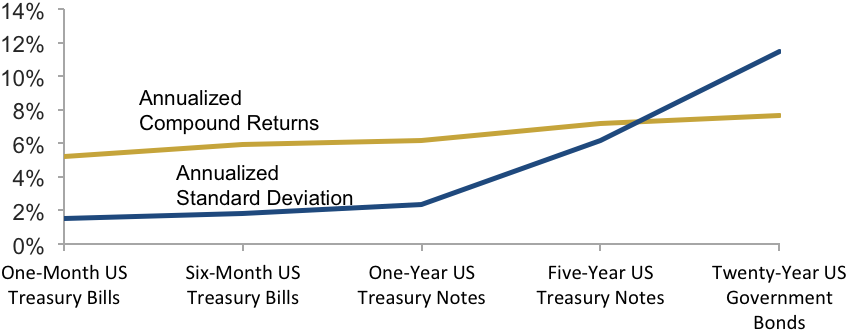

Diversification should be thought of on a global scale as interest rate changes do not happen in lockstep from country-to-country. This can introduce an additional dimension of risk, however, in the form of “exchange-rate” risk. For example, if you own a bond issued by the British government and the value of the dollar rises relative to the British Pound, the dollar-value of that bond will fall. This risk can be mitigated by using futures contracts and other types of “derivatives.” Target maturities, meanwhile, will potentially be influenced by the prevailing level of interest rates at any given time. However, as you can see from the chart below, over the long run, bonds with maturities beyond five years add volatility without adding significantly to returns. The chart shows the annualized compound returns and associated volatility of bonds with varying maturities based on data from 1964 to 2012. As you can see, volatility continues to rise as maturities get longer, even as the annualized compound returns flatten out. Finally, choosing bonds with a high credit rating will minimize volatility as the highest rated issuers tend not to see as many rating changes as lower-rated bond issuers.

The Role of Bonds in a Diversified Portfolio

After the foregoing discussion, it should be clear that the upside potential for bonds right now is limited, and the potential risks are great if one reaches for yield by stretching maturities or lowering credit quality. That might leave you asking why anyone would want to own bonds at all. At Yeske Buie, we think of the role of bonds in a portfolio as a stable reserve that can act as a bridge during a cyclical downturn in the stock market. Such downturns can be very harmful if, during a period of falling prices, an investor is forced to sell an ever larger number of stock fund shares in order to meet a fixed spending target. This can lead to a situation where, once the bottom is reached, there are too few shares left to fully participate in the subsequent recovery. If one has established a stable bond reserve that is large enough to support one’s spending needs for at least six or seven years (our typical target) such downturns needn’t be nearly as hazardous.

In order to fulfill the role just described, however, one must make full use of the risk management techniques we’ve discussed. Only then can one rely upon the bond allocation in our portfolio to be that “stable reserve” that can bridge the occasional downturn among stocks. This is why we focus on high-quality, short-maturity, globally-diversified bond funds to meet this important need. And because we’ve designed this allocation to be resistant to the corrosive effect of rising interest rates, we have fewer concerns about rebalancing and reallocating our appreciated stock funds into a bond market that otherwise seems “expensive.”