Noisy Signals

The US economy has entered its 11th year of expansion, now the longest on record. This by itself isn’t significant, some expansion always has to be the longest, and being the longest doesn’t automatically mean imminent demise. Such a milestone does leave the commentariat looking for signals, however, and for better or worse, economic signals are noisy. They have what engineers call a low signal-to-noise ratio: the amount of background noise is high relative to the signal we’re trying to observe.

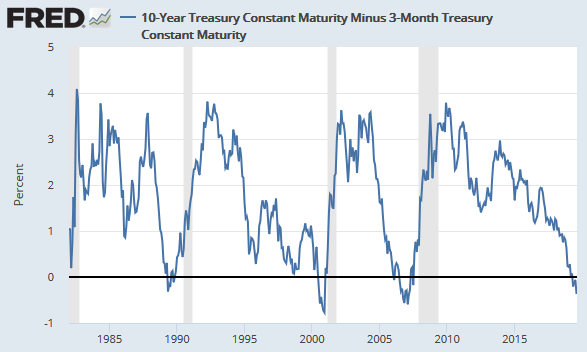

Right now, the biggest news seems centered on the appearance of an “inverted yield curve,” which happens when longer-term interest rates are lower than shorter-term rates. You may have already read that this condition has preceded every recession of the past 50 years, while giving only one “false positive” signal. This would be a much more impressive statistic if there had been more than five recessions in the past 50 years. That’s not exactly a statistically significant sample size. With so few data points, we’re left to ask why we get inverted yield curves and why they may have preceded prior recessions before we place too much weight on the current iteration.

Most of the time, the Federal Reserve focuses on manipulating short-term interest rates, generally through its control over the Federal Funds Rate. Meanwhile, longer-term rates are set by bond investors through their buying and selling in the market. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the Fed set out to control both short and long rates, the latter through a process known as Quantitative Easing, or QE, wherein the Fed steps in and starts buying large quantities of longer-maturity bonds, driving up prices and driving down rates. Longer rates may be set by bond investors, but no one is a bigger buyer than the Fed, if it chooses to be. When the Fed ended its period of Quantitative Easing, the 10-year Treasury Note’s yield began rising, moving from about 1.5% to over 3% by late last year. At the same time, the Fed started raising short-term rates back toward “normal,” which it was defining as something closer to 3% rather than the virtual 0% it had maintained since the Great Recession. It got as far as 2.5% before pausing, while the 10-year Treasury’s yield has recently slid back to 1.5%, presumably on expectations of continued low inflation (bond investors hate inflation) and the prospect of slower economic growth, of which more in a moment. The Fed, meanwhile, has reversed course and begun lowering the Fed Funds Rate again, recently dropping it a quarter of a percentage point. That reduction left the Fed Funds Rate, 3-month Treasury Bill, and 2-year Treasury Note all yielding more than the 10-year Treasury Note, an “inversion” on all fronts.

The main point is this: when short rates get higher than longer rates, it has usually been due to the Federal Reserve spiking short term rates in order to dampen incipient inflation. So when the economy slows or slips into recession, it has often been (somewhat) by design and based on the Fed’s explicit effort to slow the things down. How does that compare to what’s happening today? After a period of raising rates in the face of strong economic growth, the Fed is lowering short-term rates again in order to bolster the economy. The combination of low growth and low inflation expectations on the part of bond investors and the Fed’s cautious approach as it reverses direction on short rates, gave us our current inverted yield curve. Is this comparable to prior yield inversions? Here’s the real answer that you won’t find in today’s headlines: we just don’t know.

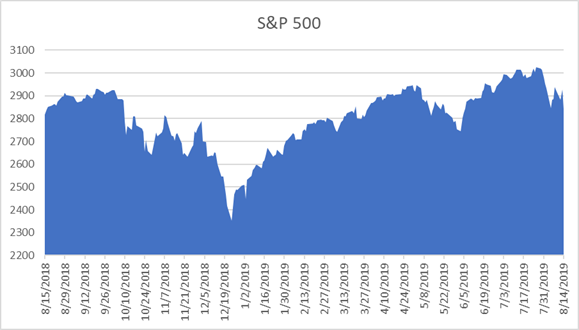

Nor do we know what to make of other noisy signals. The stock market – specifically, the S&P 500 – is one of The Conference Board’s “leading economic indicators” and it just fell 3%. Is that a negative signal and a predictor of imminent recession? Again, we don’t know. Even after the recent decline, the market is about where it was a year ago and higher than it was the year before that (and the year before that and the year before that). The full 10 components of The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index® ticked down 0.3 to 111.5 last month. Still too weak a signal to tell us much.

Here’s the path of the S&P 500 over the past 12 months. No clear signal here either.

The unfortunate reality is that we never know what these signals are telling us until after the fact. The US and world economy are simply too vast and complex and chaotic to ever be sending clear signals. This is why we need to arrange our financial affairs in ways that don’t require us to have perfect (or even imperfect) foresight.

A final note on prospects for recession. There’s an old saying that “expansions don’t die of old age,” they die because something happens. Maybe they die because the Fed raises short-term interest rates aggressively to dampen inflation and overshoots the mark, maybe there’s a financial asset bubble that grows to an unsustainable size, such as we saw with the Great Recession, but it’s never just age alone, there’s always a precipitating event or series of events.

If we were looking for a likely culprit today, we need seek no further than the ongoing trade tensions with China and other major trading partners, which have dampened economic demand and business investment worldwide. And while the Trump Administration’s complaints against China’s trade and economic policies are legitimate, using tariffs as the main instrument of negotiation is ill conceived at best. Especially so when tariffs and threats of tariffs have been likewise used against our allies, who might otherwise have formed a united front in negotiating with the world’s second largest economy. If anything has made bond investors pessimistic about growth prospects and sanguine about inflation, it is likely this more than anything else. The inverted yield curve, if it is telling us anything, is signaling distress at the attacks on the international trading system.

Unfortunately, the economic ignorance of the current US administration is so profound that we can only hope a falling stock market will get its attention. The reality is that tariffs are not a boon to the US, they are a tax on US consumers. They don’t cost foreign producers anything, they simply raise consumer prices here, thus dampening domestic consumer demand (which slows US economic growth), and production overseas (which slows economic growth there). A beggar thy neighbor approach to international trade has never worked in the past and will not work now.

So, we can obsess about noisy economic signals and what they may be telling us, or we can observe the destructive policy actions taking place in plain sight as we think about the future course of the economy. The latter is likely to provide a better indication of where we’re headed than the former.

But wait, you may be saying, Yeske Buie never ends on such a negative note! And nor do we intend to do so now. The preceding was to make clear that we’re not Pollyanna, seeing the world through rose-colored glasses. We see the negatives and are aware of the risks. But we also continue to believe in the fundamental resilience of the system, the human system, that we call the US and world economy. If things get bad enough, countervailing forces will emerge. The pressure on the US administration, including from stock market signals, to reengage with our trading partners in a more constructive way may cause a shift in strategy. Congress may reassert its traditional control over trade matters, previously delegated to the executive branch but still part of its mandate. Ultimately, we may see a change to an administration more anchored to economic reality. And don’t count out the Fed, which is keenly aware of the dangers of ill-conceived trade wars, one of the major reasons it has reversed course on rates.

Ultimately, we can all ride this out, as long as we’ve made prudent financial arrangements: an adequate emergency fund, the right kinds and amounts of insurance, effective use of employee benefits, a broadly diversified, global portfolio, one that contains stable reserves and is being rebalanced in a disciplined fashion, these are the things we can do to ride out any storm that may come.

And it might also help to turn off CNBC and CNN and instead binge watch the latest season of Stranger Things.

Don’t forget to register for our September 5 webinar, where we’ll take an even deeper dive into the current state of the world economy and what it means for your finances.