TheLiveBigWay® Digest: The Only Game in Town

We’ve been receiving a growing number of questions lately about our investment recommendations going forward. Some of these have been the result of impending retirement and concerns about preserving capital when one can no longer save from earnings. Other queries have been in reaction to the steady drumbeat of bad news concerning the US and world economy.

Whatever the source of concern, it often leads to the same question:

Does it still make sense to have such a large allocation to global stocks?

The answer to that question can be explored along several different dimensions:

- What are the real risks that investors must confront?

- What options are available to us when we choose to invest?

- What are the underlying forces that drive the performance of different investment alternatives?

And now for the Magical Mystery Tour…

What are the real risks that investors must confront?

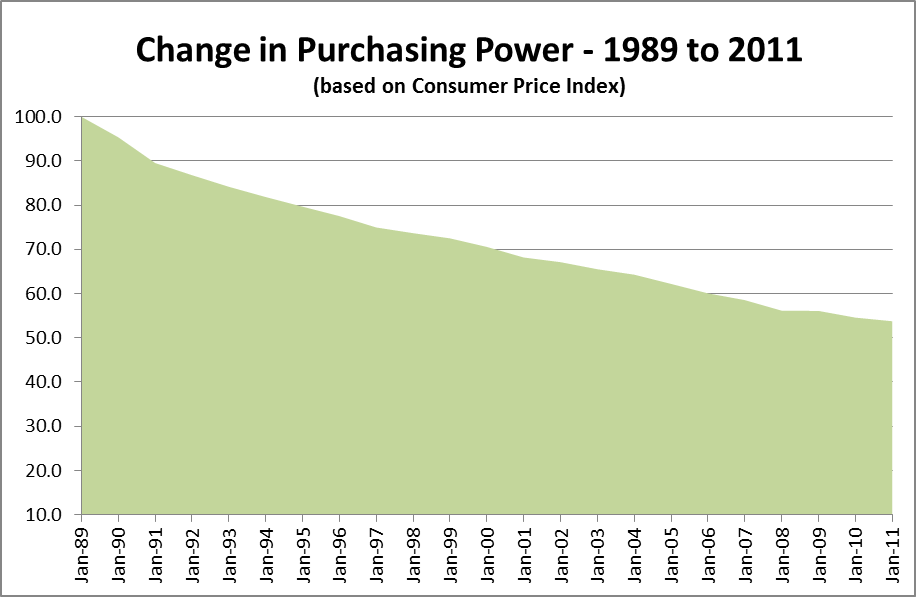

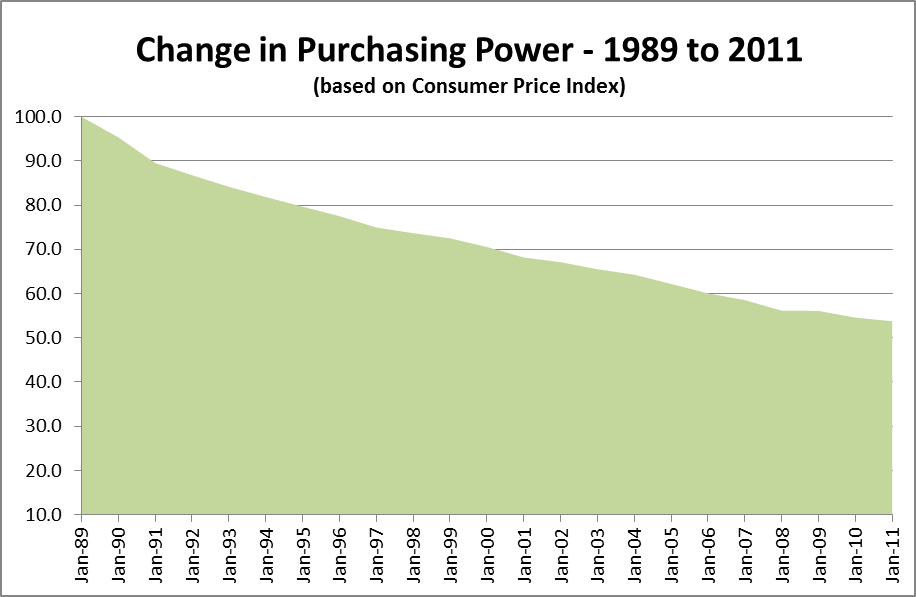

When we think about the risks that face investors, we quite naturally start with the risk of loss. We know that the value of stocks, bonds, and real estate goes up and down on a daily, weekly, monthly basis, sometimes by a lot. On Black Monday in 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by nearly 23% in a single day. The Case Shiller Home Price Index, meanwhile, has declined by 35% since the second quarter of 2006. Such losses, and the prospect of such losses, are scary indeed. However, while the value of stocks and real estate decline from time-to-time, the ultimate underlying trend has always been upward. There’s another form of risk for which that cannot be said. In fact, this other form of risk, while harder to see in the short run, goes in only one direction, and it’s a bad one. We’re talking about the purchasing power risk that arises when there’s inflation. And there’s always inflation. Notwithstanding brief periods like the beginning of the Great Depression, the inflation trend is always upward. Note the chart below, which shows inflation’s power to erode purchasing power. If you had retired in 1989 on a fixed income (as many people do), your spending power has already been reduced by nearly 50%. And here’s the really scary part: inflation over that period has averaged less than 3%. Inflation doesn’t have to soar into double-digits — as we witnessed in the late 1970s — in order to “eat your lunch,” it will quietly erode your lifestyle even when it’s averaging “only” three percent. Clearly, the mattress isn’t an option, we have to have some growth in our portfolio or we’ll be losing ground year-by-year.

What options are available when we choose to invest?

The most common investment categories are the following:

- Bonds and other “fixed-income” investments.

- Real estate.

- Commodities, such as oil & gas, grains, metals, and so forth.

- Stocks.

We’ll examine each of these in turn.

1. Bonds and Other “Fixed-Income” Investments

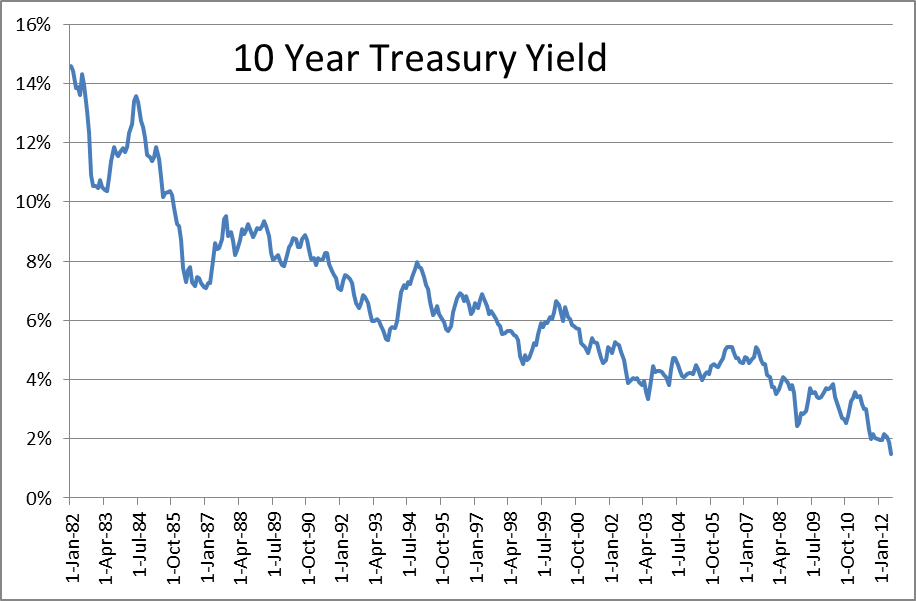

Bonds are often called a “fixed-income” investment because there are only two things that the bond issuer promises: a “fixed” periodic dollar payment (called the coupon), and the return of the “face value” of the bond at maturity. Bonds do not guarantee a particular yield, though the coupon is sometimes described that way based on the implicit yield at the time the bond was issued. For example, a $10,000 bond paying a fixed amount of $500 per year was issued with a 5% coupon. However, bonds are traded in the market and as the price of the bond fluctuates, the yield represented by the promised coupon payment of $500 will also fluctuate. And while changes in the credit- worthiness of the bond’s issuer will have an impact on its price, the single largest factor is the general level of interest rates. When investors start demanding higher interest rates, they will pay a lower price for bonds in order to capture that higher rate. In the example above, if investors are no longer satisfied with a 5% yield but now demand 10%, the price of our hypothetical bond will fall until the $500 coupon and the ultimate repayment of principal represent a 10% “yield-to-maturity.” The reverse is true when interest rates are falling: investors will be willing to pay ever higher prices for that $500 payment as their required yield-to-maturity falls. So, bond prices move in the opposite direction of interest rates and when interest rates are falling, the rising price of your bond will add to your total return. It is for this reason that bonds have been a pretty good investment over the past 30 years, during which we’ve seen a steady decline in interest rates. As the chart below illustrates, the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note has fallen from nearly 15% at the beginning of 1982 to its current level of just 1.5%. During that time, the average annual return to a constant-maturity 10-year Treasury Note was more than 9%. Not quite as compelling as the 12.5% average annual return of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Index, but very attractive nonetheless. However, we cannot be backward-looking when we contemplate our investment options. If this long-run decline in interest rates is what has made bonds so attractive, what can we say about future prospects for this category? Very simply, the party’s over for bonds. With interest rates so low, there is no upside potential going forward. In fact, bonds are likely to be a very bad performer for many years to come. High quality, short- maturity bonds still have a place in a diversified portfolio, but only as a stable reserve of value, not for any great growth potential.

2. Real Estate

Notwithstanding the popping of the recent real estate bubble, this is a category that has attractive investment characteristics over the long run. At the most basic level, real estate values tend to keep up with inflation, even when not generating investment income. The value of residential real estate has averaged a 5% growth rate over the past 80 years, more than keeping up with inflation over that period. Real estate is subject to all the same rules of investing, however, which means that diversification is extremely important. When we include real estate in a portfolio, it takes the form of a broadly-diversified global collection of real estate securities (sometimes called “REITs”) that are spread across different categories (residential, retail, industrial) and are highly marketable. The question we often receive from clients is whether they should consider buying a rental property. To this, we must answer that “it depends,” as the usual techniques of investing cannot be applied to individual properties. Obviously, there’s no diversification when buying a single rental property, and such things as unexpected repairs and vacancy rates will have a substantial impact on your results. In many ways, owning a rental property is more like starting a small business: to the degree that you can work hard to keep the property rented, manage tenant relations, and handle major and minor repairs yourself, you’ll have a better financial outcome. And while it’s true that you can hire a management company to perform these functions for you, their fees and commissions will reduce the net return to your investment. So, if you feel like opening a Mom and Pop business, by all means consider rental property, but if you prefer to have your investments working for you rather than you working for them, stick with a more broadly-diversified portfolio of real estate securities.

3. Commodities

There are two ways of thinking about commodities as investments. First, there’s a very real sense in which every company is either a producer or consumer of commodities. Which is to say that fluctuations in commodity prices will manifest themselves as fluctuations in stock prices. When oil prices are rising, for example, shares of Exxon will go up and shares of airline companies – huge consumers of petroleum products – will go down. When oil prices are falling, the opposite will happen. So, value investors like ourselves see commodity cycles as one of the natural drivers of the value investing process, where we (or one of our Dimensional Fund Advisors portfolios) will be buying the depressed shares of companies on the wrong end of a commodity cycle and selling those on the other. Commodity price fluctuations aren’t the only thing that cause companies to become “value stocks,” but they’re certainly one of them. Related to this, it’s important to note that commodities don’t really represent a true “asset class” as we like to use the term. We think of asset classes as groups of investments subject to some common underlying economic phenomenon. Commodities like oil, wheat, and gold, on the other hand, share only a common sensitivity to inflation, there’s nothing else that links them. This means that when buying a “basket” of commodities, you’re missing the chance to tease out the kind of unique opportunities that emerge when your exposure to commodity cycles is more driven by your value-investing strategy.

The second way to think about commodities, is as a resource that has generally had a zero to negative return in the long-run. The simple fact is that commodity prices have tended to fall over time, generally in response to human ingenuity and improvements in technology. The U.S., for example, is headed toward energy independence because of surging production in oil and natural gas due to new technologies. This is not the visible trend of a few years ago and someone making a simple linear extrapolation would have missed the mark by miles (see Fareed Zakaria’s piece on this). Dylan Grice of Societe General (SoGen) makes this point very well:

“A bushel of wheat, a lump of iron-ore or an ingot of silver today is identical to a bushel of wheat, lump of iron-ore or ingot of silver produced one thousand years ago. The only difference is that they’re generally cheaper to produce because over time, human innovation has lowered the cost of production. When you buy commodities, you’re selling human ingenuity.Past performance is no guarantee of future results, obviously, but human ingenuity has a good track record of overcoming nature’s constraints so far. A commodity bull market is really just a bottleneck and as a species we’ve succeeded in bottleneck removal. Historically, most bull markets have ended up where they started.”

So, the bottom line is that commodities have no intrinsic value, only value in use. Diligent value investors will harness commodity price cycles through the stock market, doing so in a much more sophisticated way than simply buying unrelated “baskets” of raw materials.

4. Stocks

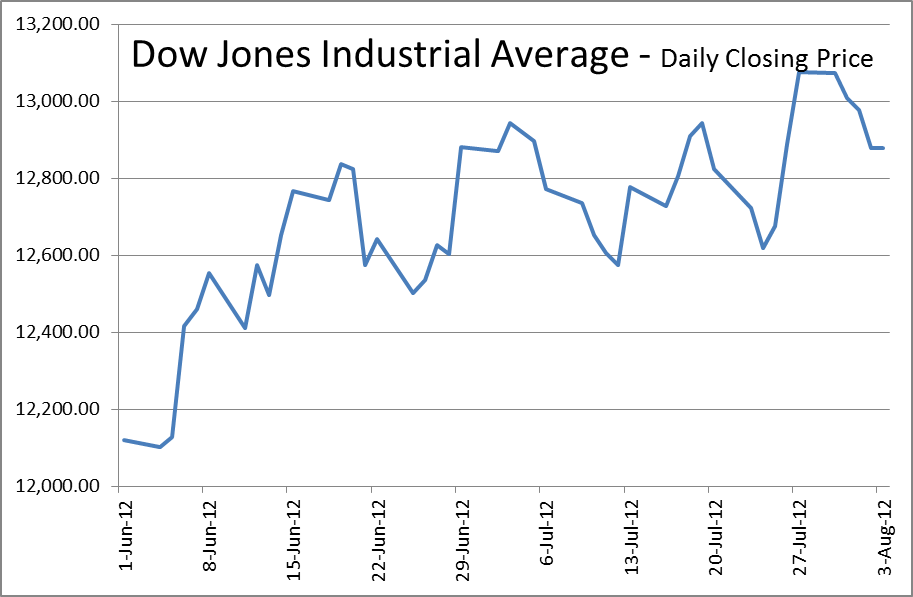

Finally, let us consider stocks, the category that seems to have the greatest capacity for scaring people. The chart below shows the daily price movements of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since the middle of June and, notwithstanding the upward trend over that time, one cannot help but note the wild gyrating path it follows. Statisticians call this pattern a “random walk” and random it surely is.

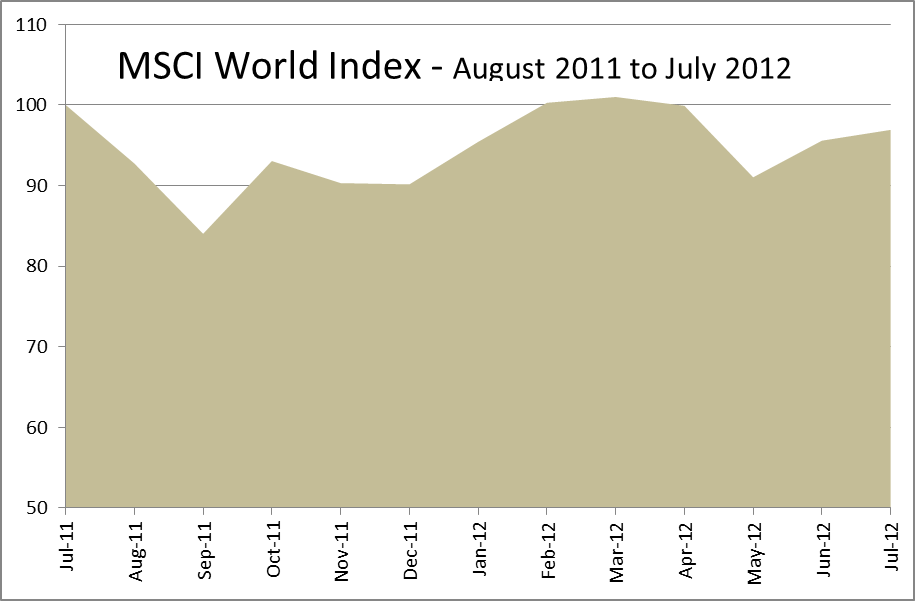

The daily swings represent the market digesting daily news as it rolls off the ticker. Since the greater part of such news is of transient interest, it gives us very little information about the long-term underlying direction of the market (on this point, you may recall our dog versus dog walker analogy). The only way to see evidence for a persistent trend is to step back and expand your scale. Beyond the chart above, we could look at the performance over the past year of the MSCI World Index (MSWI), which reflects the performance of developed stock markets the world over and is an appropriate benchmark for a global investor. As you can see in the chart below, the MSWI was down about 4% over the past year.

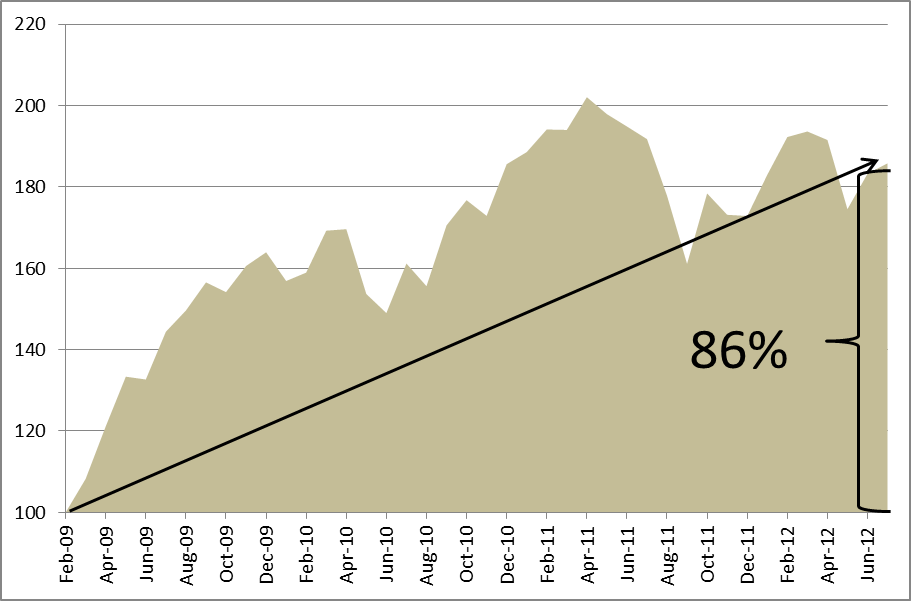

If we expand it further, and look at performance since March of 2009, you see a very powerful positive trend, with the index rising nearly 90% over that time, notwithstanding the peaks and valleys along the way.

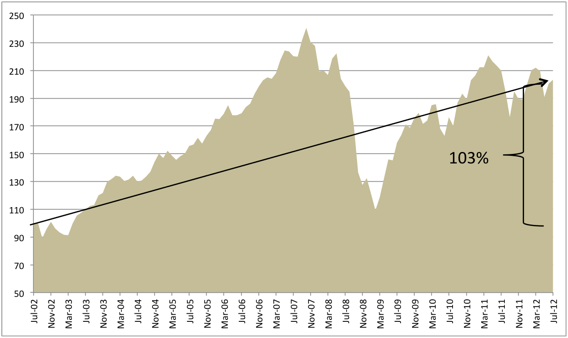

One might object that the preceding chart is so impressive only because it shows recovery from a terrible downturn. This is true, but even if we expand the timeframe further to encompass that downturn by looking back 10 years, we still see a strong positive trend. The MSWI more than doubled over the past decade, which represents an annualized rate of return in excess of 7%. Not bad for a decade that included the worst economic downturn in the past 80 years!

We prefer not to blindly extrapolate from the past, however, and need an explanation for why this might continue. There are, after all, many bad things going on in the world, from the low-growth and high unemployment in the U.S. to the rolling disaster in the euro-zone. Why should we have any optimism about the future of stocks? For the same reason that you don’t want to bet on commodities: human ingenuity. Stocks are the only investment instrument available that allows you to put a bet directly on human ingenuity. And value investing ups the ante and is an even bigger bet on human ingenuity. One of the reasons that value investing works is this: when a company gets into trouble and its stock price suffers accordingly, the people who staff that company tend to adapt, working to overcome whatever bad circumstances have come their way. And, more often than not, these people find viable solutions and the company’s fortunes recover, along with its stock price. Not every time, but most of the time. This is why diversification is so crucial, you need to spread your bets in order to capture the average propensity to succeed and recover and not be unduly exposed to the fortunes of one company or industry.

Another way to think about stocks is that they represent ownership of the productive assets of the economy. And the US and world economy have a powerful propensity to adapt and grow and thrive. Stocks ultimately rise because of this underlying goodness in the economy. It’s important to remember that the economy is just you and your family and your friends and everyone you know going about the business of earning and saving and spending and investing. All of those individual decisions aggregate up to what we call “the economy.” And human beings are resourceful and they adapt and this is the source of the economy’s resilience. Yes, we sometimes hit difficult patches and the adaptation takes a little longer, but you cannot afford to bet against it. In the U.S. right now, one of the reasons for the slow growth we’re experiencing is the virtuous behavior of consumers as they recover from the excesses of the past. Households today are spending less than they earn, paying down debt, building savings, and improving the health of their balance sheets. At the level of the household, this is a virtuous adaption, though it means that full economic recovery will take a little longer.

So, to summarize our discussion so far: bonds are fixed obligations that do not capture the upside potential of the issuing company, shifting only in response to interest rate fluctations. Bonds are also at the end of a 30 year bull market that cannot continue. Real estate, on the other hand, has attractive qualities as an investment, but is, like all other investments, best held in a diversified, marketable form. Buying and managing individual rental properties is sometimes more like a job than an investment. Finally, commodity cycles are best exploited through the stock market as part of a disciplined program of value investing. Over the long-run, commodities have an expected return of zero and owning them is a bet against human ingenuity. The only asset class that allows you to directly capture the underlying goodness in the U.S. and world economy and to make a direct bet on human ingenuity is the stock market. We may not like the daily, weekly, monthly gyrations, but it’s the only asset that gives us hope of reliably beating inflation, building a nest egg, and maintaining our standard of living in retirement.

To paraphrase Winston Churchill’s statement about democracy: the stock market is the worst place to put your money, except for all the others! Or, to put it another way, it’s the only game in town.

Sincerely,

The YeskeBuie Team