The Dividends Pros and Cons-versation

Our Clients’ portfolios receive most of their annual dividend income in December, and in anticipation, our CIO, Yusuf Abugideiri, and budding investment expert, Tim Connolly, discussed dividend investing. In their thoughtful yet light-hearted exchange, Yusuf and Tim explore why dividends can feel so rewarding and how they actually impact your portfolio. What follows is their friendly debate which we hope you’ll find helpful in understanding how we turn investing insights into purposeful strategies designed for you.

The Appeal of Dividends

Yusuf: Let’s begin by setting the table with some context and some real, objective appreciation for dividends. Tim, you’re going to have to help me out here.

Tim: Absolutely. “Dividend Investing” is one approach to designing a portfolio that we hear about relatively often. Specifically, this approach constructs portfolios to maximize their cashflow. The idea here is that a company’s dividend policy gives insight into the company’s future performance. The appeal is obvious — who doesn’t like getting paid from their investments while they’re continuing to grow? Dividends feel like finding money in your pocket, and research backs up this feeling: people treat dividends differently than capital appreciation (the growth rate of one’s investments) or capital gains distributions (the realized gains an investment pays out to its investors), even when they are effectively the same1.

Yusuf: Thank you for that, especially that last bit, as you’ve provided a perfect setup for me to make my point: dividends are NOT found money. And a preference for dividends over capital appreciation (or capital gains distributions) is almost like preferring $10 in your right pocket over your left pocket. While you may have a favorite pocket to put money into, as investors, we don’t let favoritism dictate our behavior. Let me explain:

- Let’s pretend that the share of stock is worth $1.

- Then the company announces a dividend of $0.05. When the dividend is credited to my account, this is what happens:

- I receive cash ($0.05).

- My share of stock in the company is REDUCED by the same amount, so now I have $0.95 worth of stock. I’m already upset because now I have less money invested in the market.

- To add insult to injury, note that I started with a dollar’s worth of stock, and now I have five cents of cash and ninety-five cents of stock, leaving me with… a dollar.

- But here’s the rub: now I have a tax bill, because dividends are taxable income.

- So, if you’re keeping score at home, that’s less exposure to potential upside in financial markets and more taxes due. My hate meter is rising.

Tim: I appreciate that explanation, thank you. And I don’t disagree with anything you’ve shared here. I might offer a counterpoint, though. We believe dividends are a necessary component to our Clients’ portfolio’s returns, right?

Yusuf: Yes, of course – please proceed.

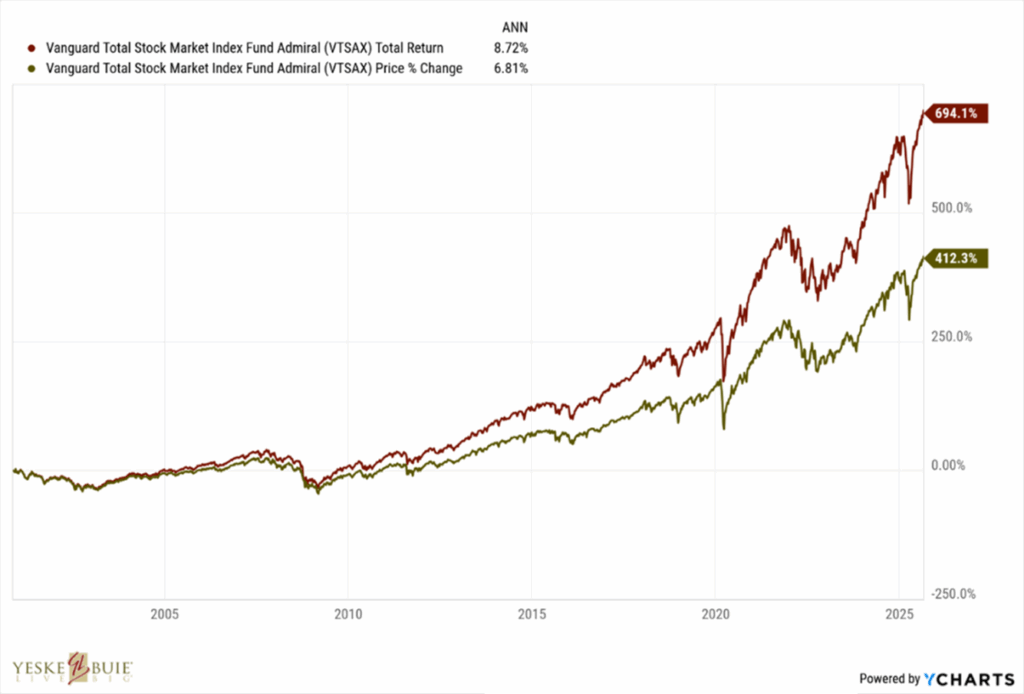

Tim: They’re an important source of returns alongside capital appreciation and capital gains distributions, and they make up a substantial portion of the returns we can observe in the market. I put this graph together for you to illustrate this point (Figure 1). Dividends accounted for nearly 2% of market returns year-over-year the last 25 years. Just putting that out there.

Yusuf: I appreciate you pointing that out. And I’ll say here that in our Clients’ retirement projections, we assume a 2% dividend rate as a component of their portfolio’s annual returns, which aligns with the real-world data you’ve provided here and with the long-term performance of the Yeske Buie portfolio of stocks and bonds.

However, I’ll add that building a portfolio with a primary focus on dividends can create issues like:

- Conflating dividend income with spending capacity;

- Inefficiency when making distributions in retirement (partially dependent on the type of dividends one is receiving, and partially dependent upon one’s account settings); and,

- A lack of emphasis on diversification, which should take precedence over the preference for investments that pay dividends.

Tim: Hmmm. Income as an issue? Say more!

Yusuf: Some conversations with Clients approaching retirement begin with the assumption that they’ll have a portfolio of investments in retirement that will provide dividends and interest at a rate that will support their spending needs. But, as readers of this digest know, our Safe-Spending Policies provide an initial target rate of spending that is more than double that of the dividend rate quoted above (5% > 2%), and the interest from their cash holdings certainly doesn’t make up the difference. So, limiting your assumptions about spending capacity to dividend income hamstrings your lifestyle unnecessarily.

Tim: Completely agree. And what do you mean by ‘inefficiency’?

Yusuf: It’s important to note that there are two types of dividends one can receive in their account – qualified and non-qualified. Qualified dividends are taxed at preferential capital gains tax rates (0%, 15%, or 20%, depending on your other sources of income). Non-qualified dividends are taxed at ordinary income tax rates (as high as 37%). We don’t discriminate between the two, as we can’t control the type of dividends our Clients receive. But we do want to point out that dividends don’t just fall out of the sky without any strings attached (at-taxed?), and a focus on generating dividend income in a portfolio can lead to inefficient tax outcomes, since gains from the sales of investments that have been in a Client’s account for a year or more are all taxed at those preferred (read: lower) capital gains tax rates.

Tim: That’s a terrible tax joke, although if you’re making a joke about taxes there’s very little upside – aren’t you supposed to be all about upside? And did you say something about a Client’s account settings contributing to this discussion?

Yusuf: I did. If your dividends are set to be reinvested in the same investment that issued them, you create a new tax lot every time you receive a dividend. All that means is that you re-set that one-year timer for a portion of your investments every time you reinvest a dividend.

Tim: I don’t like that – sounds ‘taxing’.

Yusuf: I knew you’d come around (to the jokes, too). That’s why Yeske Buie’s Clients’ accounts are set to have dividends credited in cash, giving us control over how we deploy them. We might let them aggregate so that we can make a purchase of one or two investments to rebalance the portfolio without having to sell an investment (thereby saving us from generating a taxable gain). Or, for a spending Client, we might just let the dividends build up and support some of their distributions, saving us from having to realize a taxable gain yet again.

Tim: Love that. There was a third point – diversification – say more on that point.

Yusuf: It’s more about what’s driving the design of the portfolio. We take dividends as a given, not a feature to build around or chase. We want to invest our Clients’ assets in a portfolio that is broadly diversified, geographically neutral, and intentionally tilted in favor of small company stocks and value stocks, because there are deep regularities that demonstrate those stocks should perform well relative to their counterparts in the long run.

If those stocks also issue dividends, great. If they don’t, fine. As long as they’re appreciating, we’re in good shape. And if you believe that markets work, the value and the spending capacity that is perceived to come with dividends will emerge from the portfolio organically. What’s more, is that we can find opportunities to harvest that growth as efficiently as possible on our timeline, not that of a given company’s board of directors. Corporate dividend policies don’t remain constant over time, and they tend to decrease dividend rates drastically during years of poor performance2. I’d rather design a distribution plan around an evidence-based, stress-tested approach than be at the behest of a table full of Wall Street Suits.

Tim: Fair points. And I’ll add that, dividend-focused portfolios typically have fewer holdings3 especially compared to the thousands of stocks in the diversified portfolios that underpin our Safe-Spending Policies (12,000+ at last count). To your point, broad diversification bakes resilience into a portfolio and helps maintain stability should a particular holding take a dive, a feature many dividend-focused portfolios can lack. As we often discuss in our Financial Planning Team meetings, we know there will be financial and economic downturns, it’s just a matter of when; our Clients’ spending plans should be resilient in response to that reality.

The research does support your assertion (and horrible tax joke) that dividends are not free money4. When examining how to explain historical stock returns, a company’s stock performance is largely explained by its valuation and its company size5, and not its dividend policy (which has been specifically tested).

Yusuf: Did you just use research to dunk on me and simultaneously provide a counterpoint to your own point above?

Tim: I’m glad you’re paying attention. I completely agree with you that we should consider dividends as just one source of return, and the diversification risks you’re highlighting are worth focusing on a bit more. On average, from 1963 to 2019, only about 50% of US companies paid a dividend6. Today some of the most popular dividend-focused portfolios hold fewer than 100 stocks (and the 12,000+ stocks in our portfolio outpaces 100 by a mile).

Diversification is a feature; we want investments in our Clients’ portfolios that zig when others zag, as that mitigates risk in a mathematically proven manner. On top of holding fewer companies’ stocks, dividend-focused portfolios have a type: they tend to be large established companies in mature industries. I’ve previously examined how diversification affords investors the ability to hold all the poor performing stocks of the world as long as they hold all the extraordinary stocks, too. Though dividend-focused portfolios often emphasize value stocks (perhaps unintentionally in their search for dividends), they sacrifice diversification and tilt away from small companies. The concentrated nature of dividend-focused portfolios increases the risk of missing out on returns that would have otherwise been captured by a more diversified portfolio.

The Bottom Line

Yusuf: Ok, so we’ve heard each other out and have arrived at the end of this dual-diatribe disguised as a dialogue. Where do we stand?

Tim: We’re in agreement: dividends are a necessary component of a savvy investor’s portfolio, but they shouldn’t drive the design of the portfolio. Even with keeping tax efficiency implications in mind, that’s not a consideration worth planning around (other than making sure dividends are credited to your account in the form of cash and not reinvested). And it sounds like you don’t hate dividends, Yusuf, you just hate the story that’s been told about them and how that story can sometimes get in the way of our Clients understanding how their portfolio is serving them.

Yusuf: I couldn’t have said it better myself. Maybe we’ll do this again sometime?

Tim: With the year Bitcoin has had, what are your thoughts on cryptocurrencies?

Yusuf: Oh, I can’t wait for that one!

Sources

- HARTZMARK, SAMUEL M., and DAVID H. SOLOMON. “The Dividend Disconnect.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 74, no. 5, 2019, pp. 2153–99. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45213954. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- global-dividend-paying-stocks-a-recent-history.pdf

- ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats ETF (NOBL) has 72 holdings. Vanguard High Dividend Yield Index Fund ETF (VYM) has 582 holdings. Schwab US Dividend Equity ETF (SCHD) has 582 holdings. Schwab International Dividend Equity ETF (SCHY) 161 holdings. Vanguard Internatl High Div Yield Index Fund ETF (VYMI) has 1647 holdings.

- Miller, Merton H., and Franco Modigliani. “Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares.” The Journal of Business, vol. 34, no. 4, 1961, pp. 411–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2351143. Accessed 12 Sept. 2025.

- Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. “Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 33, no. 1, 1993, pp. 3–56.

- Yields of Dreams: A Closer Look at Dividends